A post about the balance between objectivity and subjectivity in classical chess

A week ago, I was preparing my girlfriend for her tournament games.

Since most players have some level of tournament anxiety (congrats if you’re a cool-blooded unicorn), we were working on disassociation.

“Remember, at the board, you’re not you” I said. “You’re a chess machine. Without fear, finding each move like you’re crunching equations.”

Just as I said it, I felt guilty; is this really how players think? As a mantra, it may help overcome the nervous system and the stress of chess.

Yet even Grandmasters play moves based on some emotional evaluation. Moreover, sometimes they play moves that are meant to pose awkward problems for the opponent, even if the move isn’t fully sound or best. So when should we be objective and embody that “chess machine” and when should we cheat by playing “human” moves?

Don’t skydive without a parachute

When it comes to defending, chess engines contributed tremendously to our understanding of defensible positions and defensive resources. After seeing the miserable god-awful positions that computers have no qualms defending, we realized that it takes a lot to lose a chess game. Yet we often forget that even though a position is defensible in theory, it takes an engine to defend it in practice. We don’t have the parachute of eternal patience, vigilance, and calculation that engines do.

To start off, does this position ring a bell? In the Traxler Counterattack, modern engines proved that white can take Nxf7 and live to tell the tale after Bxf2. But what does it require? Moves like 11.Rh4! just to get a playable position. If you want to play like an engine here, I reeeeeeeealy hope you’ve been practicing walking on tightropes.

In this position, life isn’t a picnic for black. Our pieces are passive, we’re squeezed for space, and Bd4 is coming after which the long diagonal collapses. Leela suggests the horrifying 28…Bc3 which for starters allows them to sac the exchange with Rxc3 and ravage our kingside. Defensible? If you calculate hundred million moves a second. Leela also suggests 28…g5, after which 29.f5 leaves us with even more problems including the weakened roof and the protected f5 passer. Defensible? If you’re an electronic Buddhist monk. Finally, it suggests 28…Kf8 which I won’t even try to explain. 28…h5 is ranked by Leela as 3-5th line, depending on how long you let it run. Yet it’s by far the most human of the bunch, as it addresses the problems of space and the lack of counterplay. From then on, white needs to be very precise in order not to run into trouble himself, whereas after moves like …g5 any reasonable move for white keeps a pleasant advantage.

Don’t bite off more than you can chew

Humans are best when material is balanced and the position is rational or at least understandable. Some positions don’t cooperate in this manner, at which point human players are lost at sea; no positional compass or clues can guide you towards the shore. These positions are risky, and even if the engine claims they’re good, you might want to steer clear of them if you don’t want to get shipwrecked. Unless you think your opponent will hate this even more!

https://lichess.org/study/6GFuCR47/UaNcDXfU#12

According to Stockfish, this position is +.2 for white. But that means basically nothing here, as no human will be precise enough to nurse that advantage while scrounging for his/her missing rook.

Erken (playing white) messed up the move order just a bit, going for 14.Bh3 instead of 13.Bh3. In rational positions, this little difference will either transpose or be a small inaccuracy which won’t matter much. Here, this switcheroo fiasco is a game-changer as black gets to develop and consolidate his extra material. The normal-looking “sensible” moves like 21.Rxh1 were amazingly a mistake in this upside-down world.

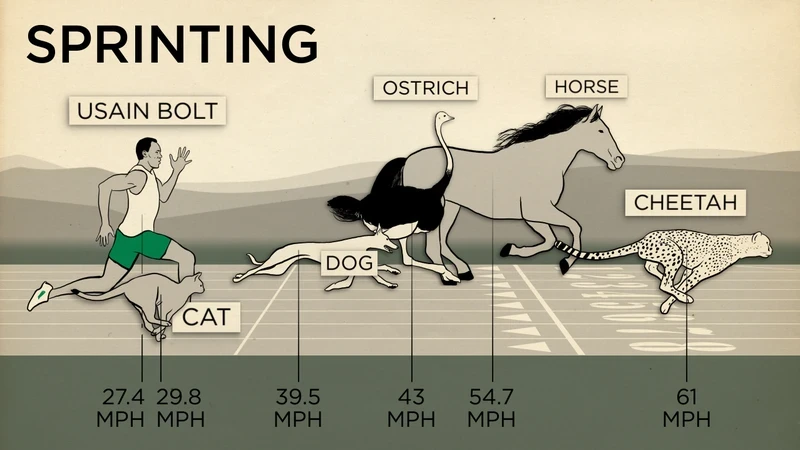

It’s a good thing AI hasn’t taken over hot-dog eating contests (yet).

Don’t try to run faster than a cheetah

With the advent of neural networks, we found out that engines were more comfortable with speculative sacrifices than grandmasters. As Kasparov put it in an interview, as humans started playing more solid, computers became more wild. The first reason for this is Alpha Zero’s ability to feel the resulting positions and recognize that the material sacrificed was worth it for one reason or another. Yet another reason was its ability to play a series of attacking ‘only’ moves in a row, whatever the position needed. No tactical blow, no combinational finish was missed which is more than most humans can claim.

Here’s an example of what happens when humans try to play computer attacks:

8.h4 was roughly the extent of my prep here. The funny thing is I consciously rejected the first engine line 8.d4 as the resulting positions were awkward for the white king and hard to defend. As for pushing the h pawn, how hard could that be? Very hard as it turned out, as every single white move afterwards was either an inaccuracy or a mistake. The computer wants to attack with paradoxical moves, for example 10. Qe3!? provoking Ng4 (putting their knight on a seemingly better square) before retreating the queen. Go figure! ‘Normal’ moves like 16.h6? were rewarded with a losing position for white at move 17! I was lucky that my opponent believed in white’s ‘compensation’ and accepted an early draw offer.

Maxime Vachier-Lagrave is a fantastic player who went for the principal line in this middlegame and got a menacing attack. The engine insists white has a winning advantage, but the way through this forest of variations is so immense that even Maxime couldn’t pull it off. In this position he needed to find 30.Qh4! Qxe5 31.Nc2!! to secure the win. Talk about computer resources…A great quote comes to mind; “Chess is about solving too difficult problems with too little time”.

Does that mean we should shy away from all sharp positions where we can’t play like engines? No! My suggestion is find sharp positions where it’s easier to play for you!

The value of easy moves

An engine evaluation is very one-sided. It doesn’t reflect how hard it is to find the following moves after its recommendation. Nor how big the margin for error. Nor the variations you have to calculate to keep afloat in the moves to come. This can make it misleading.

Once upon a time, King Croesus from the Lydian empire went to the Oracle of Delphi, and asked if he should attack the Persian empire. The Oracle told him that if King Croesus crosses the Halys river (into Persia), a great empire will be destroyed. The arrogant king took that as a sign of encouragement, and attacked Persia. Little did he know that it was his own empire that would be destroyed…

In the same way, we may follow engine recommendations blindly, only to end up destroying our own armies. This is where the easy moves concept comes in.

Last week, the Toronto Open concluded with this fantastic attack from Anthony Atanasov, who went 6/6 crushing all resistance. A part of his success was getting positions like this one, where despite the missing pawn, white’s moves just comes easier. At some point, white will play Nde4, Rde1, double up on the e-file, f4-f5, and sacrifice a knight near the enemy king. Meanwhile, black has to bend over backwards and put their pieces into all kinds of weird squares; Rh6-Rf6, bishop back to c8, and king…heaven knows where. The margin of error for black is infinitesimally smaller than white here. Even if Nikolay had chances to come back into the game somewhere, he’s walking a mine-field, whereas white is taking a stroll through the park.

https://lichess.org/study/6GFuCR47/6B4QCkTI#20

In the first round of that same tournament, I failed to steer my position into easy waters which inspired this article. In the position above, I had a wide variety of small advantages to choose from. 11.Bd4 looks nice, with e4 coming up. 11. Nc3 followed by e4 is also very comfy, with white’s pieces being slightly more active. My first intention which I should have gone with was 11.Qb3 after which black has to find only moves just to keep the queenside together. Only white is attacking, and life is good.

Something strange (a self-destructive impulse perhaps?) cajoled me into playing this 11.Nd4-f4 idea. Even though all moves, including Nd4, give a slight advantage to white, this was a failure in practicality. At most, I will be able to trap the bishop on g6 for a few of my kingside pawns. This will be super risky and double-edged, while Qb3 keeps a nice/steady edge where I have basically no risk at all after Qc8. These are the rare cases where the objectively best move is not necessarily the one you want to play.

Funny Stories About Engines

The most infamous case of “engine failure” in chess was of course Kramnik’s defeat by Leko in their world championship match. Kramnik’s team didn’t quite spend enough time on a position in the Spanish Marshall Attack, and Leko managed to find the hole in their concept over the board, mating Kramnik! My engine failures were similar albeit at a smaller stage: When playing my friend Zach Dukic a year ago, I was using my phone to look over some opening lines. Laptops are heavy to carry and in “wild west” North American tournaments, you’ll be lucky if you get an hour to get ready for your opponent. So I quickly found a sideline on the phone that I hoped would give my opponent something to think about. The phone engine I had in an opening explorer app insisted that the position was about equal, and resulting positions would lead to some sort of reversed benoni, an opening I was happy to see.

My opponent indeed had something to think about, as I was giving up a pawn for very little in return. I had assumed this pawn to be poisoned, considering the engine didn’t even consider taking it for black, preferring to push 6…d4 instead. Being down a pawn, It took all my effort just to equalize with white…

Fast forwarding to this July, I was playing the Calgary International tournament with the same two rounds a day format. Before the fourth round, I had taken a look at some lines at home on a reliable laptop engine. Yet by the time I had gotten to the tournament hall, I wanted to check those lines, for memory’s sake. A gaping hole was found, with the phone engine screaming its version of bloody murder (+1 to 1.5). Here I had to choose, did I trust the cursed phone engine which was casting shade upon this whole variation? Or did the computer engine simply see more, and evaluated the position better? I decided to go for it anyway, come hell or high water. Thankfully my opponent avoided this problematic hole, because the phone engine turned out to be right! Leela missed some tactics which led to a faulty assessment at home.

The meaning of chess

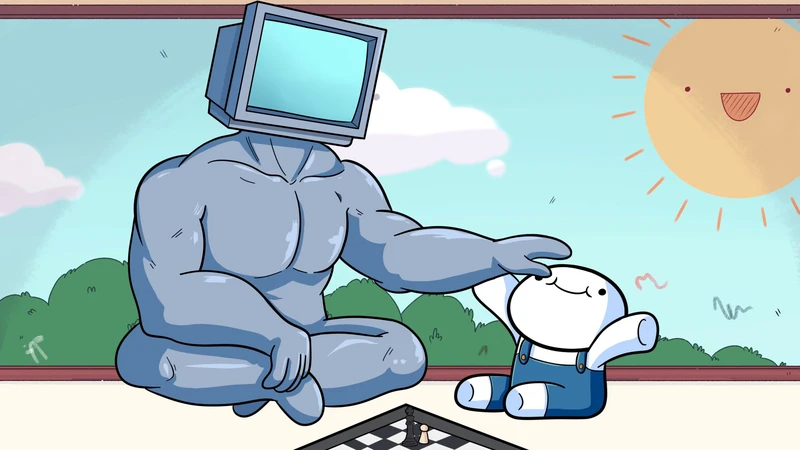

A big part of Botvinnik’s life was dedicated to early computer engineering, especially chess engine engineering. He thought that the right approach was to teach a computer how to think like a human (arguably similar to the concept of neural networks today).

Here is a story he liked to tell:

“In 1962, I was travelling to Georgia with my friend Salo Flohr. Among other exhibits, I was welcomed to their collective farms, renowned for their food. Flohr instantly had questions for the farm’s director:

‘Do you like the soccer team here, do you watch the soccer teams at the local stadium?’

‘I visited a few times, understood the secret of it all, and stopped going,’ came the unexpected reply.

‘Have you ever played chess, do you like the game?’

‘I played several times, understood the secret of it all, and stopped playing. Now I just grow watermelons,’ answered the director.

“I can take a leaf from the director’s book here,” said Botvinnik with a smile.

“If I manage to create a chess engine which will calculate chess moves, and polish it until it becomes highly proficient, maybe I will understand the secret of it all. At that point, I can stop playing chess altogether.”

Eventually Botvinnik did stop playing chess altogether, preferring to teach instead. Did he find the meaning of chess? 🙂